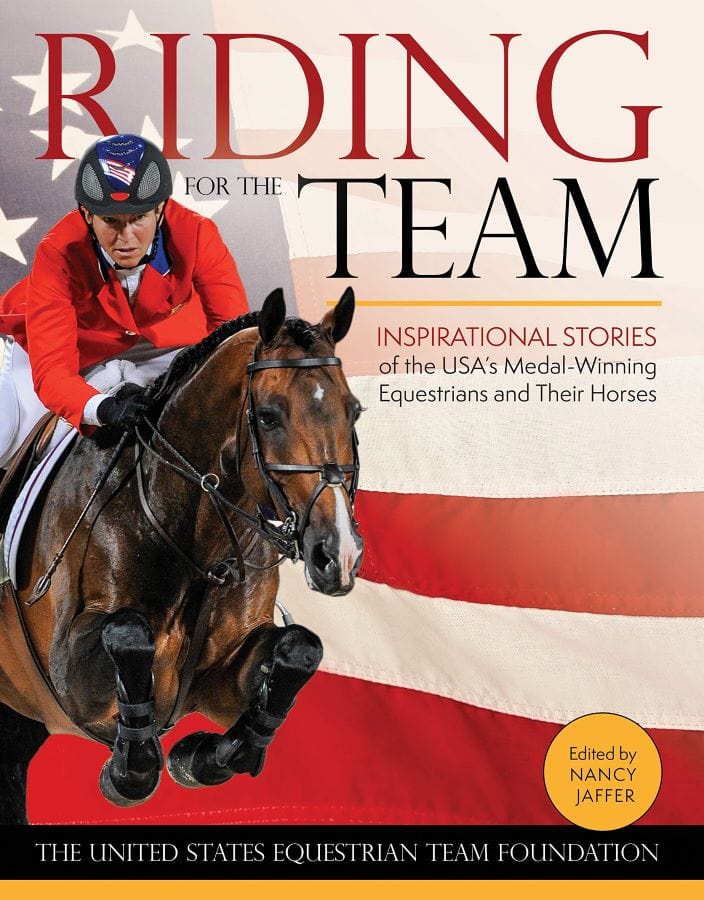

An extract from Riding for the Team by the United States Equestrian Team Foundation, edited by Nancy Jaffer and Published by Trafalgar Square Books.

(HorseandRiderBooks.com)

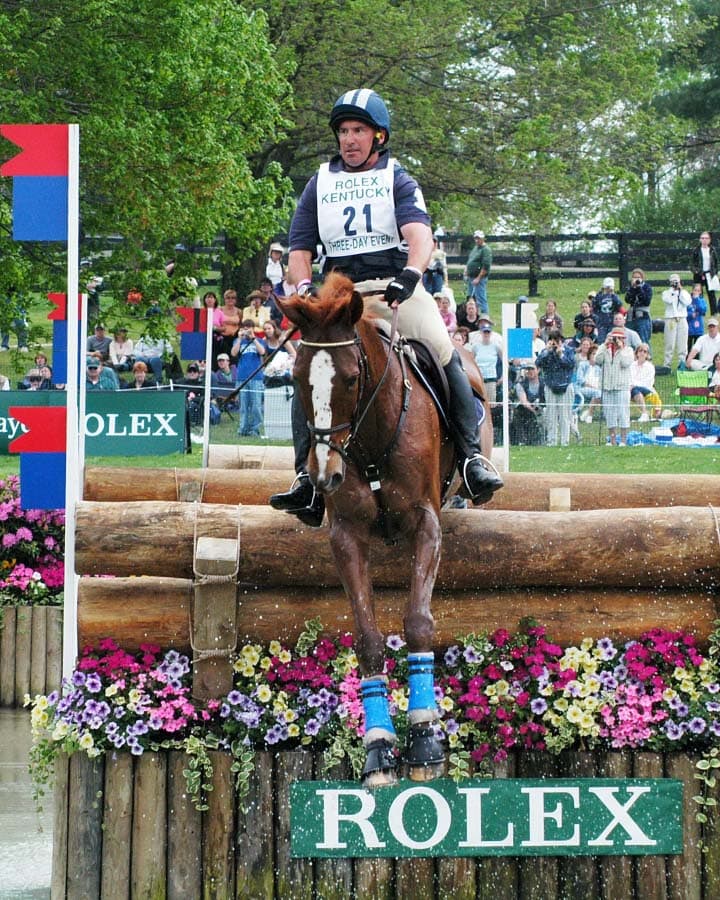

—In the words of USET Eventer, David O’Connor

Eventing is quite a different sport than it was when I started in the game. The emphasis on safety increased beginning in the late 1990s, but two decades into the twenty-first century, it came into even sharper focus.

When I did my first CCI (international event) in 1978, the fences were more substantial and upright. That era’s version of “frangible technology” was a fence that broke. Upright bounces and upright gates were a part of the game. At Radnor in 1979, an upright gate halfway down the hill caused a lot of wrecks. It weeded out half the division, but I was able to jump it and because of that, I did well and got noticed.

Cross-country definitely was the big deal, the reason for eventing. Courses were not as technical as they are today; they were more straightforward and rewarded boldness, while the endurance side was a big factor, though that diminished after it was decided to drop the long format, which included roads and tracks and steeplechase.

Dressage in those days was rather simple and straightforward. At the same time, show jumping was more influential. When I began my career, it cost 10 penalties if you dropped a rail.

In those days, nearly everyone who evented also went fox hunting, or perhaps competed in point-to-points and galloped racehorses. It was much more about coming from that background than it was a few decades later. Pony Club, for instance, was very strong with eventing. As the years went by, fewer riders had that background, and their numbers will continue to decrease as more land is being developed. There is not as much opportunity anymore for future eventers to be involved in fox hunting or racing as easily as once was the case.

In the 1970s and ‘80s, the sport was smaller and the horses usually were Thoroughbreds who tended to be in their second careers: ex-racehorses or horses that were not fast enough or too careful for steeplechasing. By the turn of the twenty-first century, more and more horses were purpose-bred for eventing. While today’s European Warmbloods would have had a hard time with the demands of the long format, dropping the speed and endurance phases suited their abilities, as a greater emphasis on dressage and the technical aspects of cross-country emerged.

In the 1960s, only two combinations were allowed on a cross-country course. Now there are 45 efforts in a CCI four-star (which became a five-star as the levels were adjusted in 2019) and no restriction on the number of combinations. It’s a huge difference, because combinations are more intense and take more effort.

The effect of the changes means eventing is a different sport than it was when I started. I’m not a person who looks backward in a way of thinking that was better or worse. It’s just different, and your job is to deal with it. That involves a skill set for riders, many of whom, as I said, lack experience riding at speed.

Doing the steeplechase was not great for the horses, and today they generally are sounder, which means in some ways, it’s a little better for them. Cross-country now is the fastest thing you do, which was not the case when we were doing the steeplechase: after going 690 meters per minute, you’d head out on cross-country and go 570 meters per minute. I don’t think Germany’s Michael Jung—the former Olympic, World, and European Champion—has ever done a steeplechase in his life. Neither have Jonelle or Tim Price from New Zealand, but they’re beautiful cross-country riders.

I don’t get into the habit of comparing one generation to another. To compare a Bruce Davidson to Michael Jung is not relevant. Today’s game isn’t the one Bruce was playing when he won the World Championship for the United States in 1974 and 1978. If Bruce were in his thirties now, he would be one of the Michael Jungs of the world.

I don’t think that kind of change is limited to just our sport, though. Think about concussion levels in football. Across society, there’s a different look at many sports than there was 20, 30, or 40 years ago. That’s just reality, and I think that’s a societal thing.

When I was president of the U.S. Equestrian Federation, we held a safety summit in 2008 after seven international riders from around the world died during the 2006 and 2007 seasons. One of the questions that we asked was, “Are there things you can do about people getting killed?” We are trying to reduce horse falls, because if you do that, you reduce rider falls. At the safety summit, one of the first things we talked about was changing the culture, which takes a while in a sport like ours.

Changing the culture is very important. Even from the time when I started, the winner sometimes was the last man standing. That’s an exaggeration, but at that time, you were able to remount two or three times after a rider fall. Even after a horse fall, you were able to just get on and go on. The orientation of finishing at any cost, which started with the cavalry, does not fit with today’s sensibilities, when it is no longer acceptable to put horses at risk in the rush to the finish line.

We are not going to stop horse falls altogether and get down to zero. The real barometer of success is: do we see that number coming down? At the summit, we asked how this could be turned around. The consensus was that one way involves riders’ responsibility in terms of not entering competitions for which they and their horses are unprepared, and admitting it when they make a mistake. The principle involved is that responsibility equals accountability. We have to be willing to stand up and say, “That was my fault.” That phrase should be used when appropriate not only by riders but also course designers.

Now, with the change in the culture, you see people who’ve had two stops just walk off the course. I think that’s all for the better. It’s better for the horse and better for the rider. And yes, there has been a culture shift. Once you have that, people buy into a thought process. The dressage phase has gotten better, but not to the level where it has had an impact on the cross-country ride unless some people overdo it. The quality of the riding in show jumping has gotten better.

It comes down to having the horses understand the questions and enjoy what they’re doing.

David O’Connor

That involves technique and communication from both members of the partnership. The horses of yesterday would have needed a completely different type of training if they were to return and attempt today’s courses, with all the corners, which were fences we didn’t jump a few decades back. If you took the course for the 2018 Tryon World Equestrian Games and threw it into 1968, no one would have gotten around it then because they didn’t train for it.

With the change in the sport, you’re seeing really good cross-country riding, really good showjumping riding, and really good dressage riding at the top levels. We’re in a refining stage now, with angles and narrow panels cross-country. Looking at what the next change will be, there are a couple of different options. I don’t believe dressage can go that much higher, though there’s probably room for a few other exercises. I can see the horse trials show jumping being a little bit bigger. There might be a look at other ways to give penalties. How do you separate the excellent from the really good? That’s a continuing process, but you can’t make jumps any narrower.

For the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, another big change in the way eventing is being run was mandated because the International Olympic Committee wanted to have “more flags,” but the same number of horses. The only way we could get more countries competing was to have fewer riders on a team. So the Tokyo format is to be three on a team, instead of four, with a substitute rider available in case one team member is eliminated.

We want teams to finish, but we don’t want to make the cross-country that much easier. So yes, you can substitute, but doing so, you can’t win. The winner is going to be the team that goes all the way through with the same riders. It’s quite different from the way eventing was conducted in other Olympic Games, but I 100-percent believe we need to stay in the Olympics—so this was what we came up with. I’m a believer in the Olympics. It has a big impact on the sport, a financial impact on the sport. And then there’s the emotional drive for a child getting into the sport. It’s had a huge impact on my life. I’ve been involved in the Olympic process since I was 18, so I’m a little biased. If we have to make some adjustments, well, so have a lot of other sports.

And this mandate is only for the Olympics. It will still be teams of four for the World Championships, the European Championships, the Pan American Games, and the Nations Cups. Looking ahead, I think eventing will survive, absolutely. The interest in the human/equine relationship is still very strong, and horses still make a difference in society. People look for games to play and people really enjoy this game. I do see the sport 30 years from now being here and riders around the world wanting to play it.

To read more from our top Team riders, purchase Riding for the Team by the United States Equestrian Team Foundation at HorseandRiderBooks.com.

For more Eventing stories, visit our Eventing page.

For more book extracts, visit our Book Extracts page.

HorseandRiderBooks.com is the storefront for Trafalgar Square Books of North Pomfret, Vermont—a small, privately-owned publisher of fine equestrian books, eBooks, and videos, craft books, and selected other titles.

SOCIAL