Derek di Grazia is the world-class eventer and course design mastermind behind the upcoming (fingers-crossed) Tokyo 2021 Olympic cross-country course. His ongoing years of international competition and course design are evident in his work today, but what shines through the most is Derek’s love of the horse and this sport that he’s dedicated his life to.

EQuine AMerica: I know that you’re a competitor as well as a designer. So how long have you been competing and how long have you been designing?

Derek di Grazia: I’ve been competing since 1968 and I’ve been formally designing courses since 1986.

(Photo credit Kim Russell/US Equestrian)

Are there advantages or disadvantages to being both a rider and a course designer? To me, I think it’s an advantage. I’ve always felt that way because I think it helps me understand what the horses are apt to do under different circumstances on course. By being a course designer, you understand the relationships from one jump to another, and as a rider, you understand how it feels to ride over different types of terrain. There are probably many, many other things I can’t even think of right now that I gain by being a rider and a designer. To me, it makes a big difference.

This may be a loaded question, but which do you enjoy doing more, riding or designing? Actually, I enjoy both of them. I’ve been doing them both for a long time obviously, and I still like to ride and compete. I really do enjoy that, but course design takes up quite a lot of my time just because of the travel and being present for the courses I’ve designed, so I don’t have as much time as I used to for competing, but I still do it.

If you had to choose a favorite course that you’ve ridden and a favorite course that you’ve designed, what would they be? That’s a very hard question! As far as the course, I actually have more than one favorite because each one is different; they’re all in different locations with different types of terrain, and they each are special in their own way. So, I can’t say that there’s one over another, and that’s actually why I enjoy it so much because there is such a variety. I think that’s what makes designing quite interesting.

Favorite course that I’ve ridden… Competing at Kentucky was very exciting, and I think probably one of my most memorable experiences. I rode there quite a few times, and the time that I was able to win was very special for me.

And then what was it like to go back and design there? This year [2019] was my ninth year designing at the Kentucky Horse Park. It’s quite an honor to be able to design at the Horse Park, especially since the Park’s changed so much over the years and it’s quite a fancy place now. They have so many different things going on there, and the facilities are amazing. From a course design standpoint, there are many different features and different ways to use the terrain, it’s quite a pleasure.

Given that one of the main things you like about course design is how many different variables there are at different locations, what is it like to design at the same location over and over again, having to keep making it different and challenging in new and different ways? Well, actually that’s another fun part of it because every year I do it I have to think about it as a blank slate. Trying to make it into a different competition every year is like putting a new puzzle together.

What did it take for you to transition from being a competitor to being a designer? Meaning, if someone wanted to do that, what would you recommend they do? Well, actually back when I did it, it was probably quite a lot easier than it is now because now we’ve developed licensing programs to license course designers, so you have to go through more of a process to become a course designer than when I started. Back when I did it, I’d get a call from someone asking me to come design a course and I went and designed the course, and then one thing led to another and I got another course and another course.

Eventually, I had to get an FEI license, which I was able to do, and then I just sort of kept going from there. I don’t know that anybody could come and do that the same way in today’s world. So, you learn a lot along the way and you keep learning. I’m still learning today; you never stop learning in this business. I always say you never stop learning when you’re teaching and training and dealing with horses. It’s an ongoing process that goes on for a long time—for forever as far as I’m concerned.

Do you have a particular mentor that brought you along in your career? There are always people helping me along the way. Even still today, if I ever have a question about something, I can always talk with them about it. And I think that, especially within the course design community, there are designers out there who are very interested in talking about course design and issues that come up as the years go by and the sport develops. I think that’s always great.

Initially, when I first started, Captain Mark Phillips was very (and still is very) helpful to me. To this day we still discuss a lot of things regarding course design and I think he’s a great mind as far as that’s concerned. So he’s been very helpful to me. And of course, when I was making my way into my position in Kentucky, Mike Etherington-Smith was very helpful to me. And he’s another designer that I feel is a great one to discuss things with. I also love to go around and look at other courses that other designers created, and I just try to learn from what they’re doing. I think you can find a lot of help in a lot of places along the way in this business.

Are you paying it forward in terms of stewardship of this career? Are there people that you are helping to bring along right now? I try—I try. I think we have to be doing that. We have to be doing it all along because we need more designers. I guess I consider myself one of those ones that are at the top, and eventually, we’re all going to age out of the sport so we have to make sure that there are course designers coming along who are going to be able to take over from what all of the other course designers are currently doing.

I think, as a sport, we have to find a way to get riders involved in course design, and this is not something new—we’ve been trying to do this for years—but I think what happens is that riders get sort of consumed with their careers because they’re competing, and I don’t blame them… It’s a fun sport! It’s the same with any discipline, whether it’s dressage or whether it’s show jumping, riders understandably want to have their careers as a rider. And of course, it does take time to become, and then to be, a course designer. But, I’m hoping that we’ll get riders more involved and interested in becoming official course designers. Hopefully, some will be able to come up through the ranks and be our next upper-level course designers.

Are there cross-country course designers who were never riders? I think most course designers were at least riders at one point. Actually, part of the licensing within the US Federation is that, depending on the license you’re trying to acquire, you have to have ridden over a certain level. So that’s just part of it. I suppose that sounded like a silly question, was thinking that being a course designer is a lot like being a civil engineer, so I wondered if it could be successfully accomplished without having a lot of riding experience. Well, as I said, being a competitive rider and a designer has been a great advantage for me. Course designing is a lot about feel. It’s not so much about the numbers (though the numbers are part of it), it’s about how you feel, how the groundworks, how the horse will feel at different parts of the course, and where you need to ask certain things. And that’s where having been a rider becomes very useful because they both sort of work together, the feel and the numbers.

It seems to me that each designer has sort of their own style, their own individual way of designing. How would you describe yours? I’d say that I like to use the terrain because I think that you can make the jumps more interesting if you use the terrain that’s naturally available. I like galloping courses. I like to develop a good flow; I think that’s important. And then it’s a matter of putting out fair questions that are safe and at the same time educational and different so that you’re not always asking the same questions. I’m trying to develop horses and riders with exercises that are appropriate for the level that they are competing at. At the highest levels, I am apt to test the rider’s ability and the horse’s training. I like to think that, at all levels I’m designing, something is being learned.

For you, how much of it is education versus testing? To me, most of it is education. Even at the highest level I still aim to educate, even though they say that at the current 5* level it’s more of a test. But, I think that even at that level they’re still learning. That’s just the way it is. Are there certain elements you put in, maybe specific questions where one is to test and one is to educate? To me, I always think about education first. So whatever I’m putting on the course is going to have an educational element to it.

Since you’ve been doing this for so long, would you say that course design has changed or evolved from say 10 or 20 years ago versus today? I would have to say that it probably has changed just because I think the changes in the dressage and show jumping events have both started to ask more of the horse and the rider. They’re basically asking the horses to be more schooled and more educated within those disciplines, so in turn, I think that the courses have become more elevated and the riders need to be more educated in how they approach riding cross country.

So, about Tokyo 2020 (now 2021)…

When did you find out that you were selected to design the cross-country course for the Tokyo 2020 (now 2021) Olympics? I think it was February of 2017. And I read an interview that you did with US Equestrian in April of 2017 that said you had already started working on the design. So even with three years to plan it, you started working on the design right away? Yes, we started right away. I think I went to Tokyo for my first site visit in March of 2017.

Why do you think they chose you? I don’t know! It’s the fourth Olympics I’ve bid for, so maybe I just hung around long enough. The bid process is such that they typically send an offer to bid to four or five designers in the world, but I don’t know how they come up with the list.

To submit your bid, do you have to show them what you would like to do? Do you send them a proposed design? Or is it based on your past design history? Do you mean the Tokyo organizing groups? Yeah them. Well, each bidding process is a bit different, and in this case, they wanted us to take a map of the area and basically show them a proposed course on paper, as far as the track and how we would use that piece of property, not having ever seen it. They did invite us to come out and see the property if we wanted to, but I didn’t go. I did the map and went through the exercise; I just did what they asked.

We had to decide on a track and illustrate where we’d position jumps on that track, but I don’t think we had to put down what the actual jumps were. And then it was quite funny because, when you actually get there and see what the site looks like, you look at what you put on paper and think, ‘well that would never happen here.’

When you first found out the committee selected you as course designer, what were the first things you did? Well, quite literally I went on my first visit to Tokyo to see the site for the first time. That’s the first thing you want to do so you can see what you’re dealing with. I arrived and first we had a big meeting, and there were more people in there than I can even tell you, but everybody had a job and they were all involved in what we were going to be doing so it was good to be able to do that. From there we all went on a tour of the site and looked at what there was to work with. The cross country is in a different location than the dressage and show jumping will be; it’s situated on an island that overlooks Tokyo Bay and the harbor. You can look right into downtown Tokyo, so it’s going to be amazing.

I think the biggest thing for me to do was to look at the length of the course, which is 5,700 meters, and try to figure out how to design it to meet the specification. So that was my first mission: to see how I could make the length of the track work. Is that time limit or track length longer or shorter than average? That’s close to what’s been done in the last few Olympics. Now it seems they want it to be right around 10 minutes when in the past it could have been a bit longer than that.

Once selected, do you join a team or do you bring a team of your own people with you? No, for course design, I’m the team. [laughs] So you get inserted into the team of developers as the designer? Yes, I was the one that was brought in to design the course and so I had to come up with the track and show them where we were going with it.

At what point did you design the full Olympic course? The track was designed in the first six months, or the first two visits really. Was this one of the more exciting courses to design? It was a challenge, but it was a good challenge. The good thing is the job is going in the right direction and that’s what’s important. The people that I’ve been working with have been great, and they have really gone above and beyond to try to do what we wanted to do. And, we’re in a good place at this point. I would say that if I think back to where we started and where we are now, I think we’ve actually come pretty far in the past three years.

(Photo credit Kim Russell/US Equestrian)

Are there issues with language barriers or anything like that? There are translators. I would say that quite a lot of people that I work with do speak some degree of English, which is obviously very helpful, but there are always translators there if you need them.

So how did/does the process unfold? The track was laid out and then from there, the site went through several different phases. We had to clear quite a lot of trees from where we wanted to lay the track. The trees had to be relocated—and they did relocate them—they transplanted all the trees. Wow, I applaud their environmental consciousness!

Then we created the track and had to get the grading correct. There are always drainage issues and other obstacles that we had to find solutions for, and we found solutions for pretty much everything. Course Builder, David Evans (England), and his team came to the course and built the permanent features and oversaw the track development. The various local contractors did the final grade work, laid all the subsoil, the turf, all the irrigation, and then put all the grass and the water jumps in. Then we were just in that phase of letting the grass grow and getting our test event course ready for the summer.

While the grass is growing, we sort of continue to play around with the Olympic course; even though most of it’s designed, we’re still making little changes here and there. Overall we’re in a good place at this point. We never know what’s going to happen along the way, but it’s all moving forward so it’s all good. So is it basically done already? Well, the track is all there so yes there’s a lot that’s done, which is a good place to be. Now it’s just building and installing the jumps, and to me, that’s the fun part. I’ll go back over to Tokyo in November and we’ll start building the actual course, and that process will probably go on until March, but I won’t stay there the whole time.

When do you expect the Olympic course will be fully completed? Probably the end of July next year. Okay, that’s close to the games. It only needs to be completely finished the day before the Ground Jury inspects the course.

You mentioned a test event. What is that exactly? Typically, most championships always have a test event the year before to test your systems and the personnel, and to run over the ground that you’re using. You don’t test run over the same track; you just run on the same ground that’s been prepared, so we can see how the footing we installed holds up and how it reacts to the horses galloping and jumping on that surface.

The test event also tests the personnel, which is a good thing to do a year in advance to make sure key personnel understand how things are going to run, including testing the timing and media infrastructure. Administratively, it gets all the people that are going to be working next year in tune with what actually goes on during a cross country day. We had a lot of volunteers come to the test event, to become familiar with what goes on. The test gives everyone a little bit of comfort before going into the Olympic year.

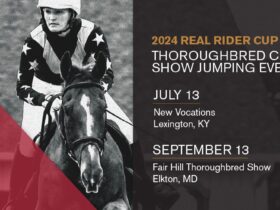

What riders was it open to? Test events are open for countries to send their own horse and rider combinations; if they want to do that, they can do that. Otherwise, the host nation will usually have some national riders who will come ride it. You don’t need huge numbers; you just need enough riders to make sure everything works. Who came out to ride the test? We had riders from Great Britain, Germany, and Australia, and then the Japanese had riders as well. It was actually a good turnout. There were very high-profile riders, a bunch that came were very experienced riders like Michael Jung (Germany) and Andrew Hoy (Australia). There were, I believe, five top Japanese riders as well. I think it was good for all the riders, as well as all the national federations that attended, which there were quite a number [including the US].

Has this been the most challenging course you’ve ever designed? I’d say it was a challenge initially, given a piece of ground that was not that large that had never been used for a cross-country course before. There were things that we had to overcome to make it into what it is today, but that’s the exciting thing about it. It is truly exciting to see the development of it as we’ve gone along.

Are you designing other courses while you work on Tokyo’s course? Yes. I have a number of events that I do during the year. And they all take a certain amount of time. How many courses are you working on right now? I actually couldn’t tell you. I haven’t really sat down and counted them, but a lot. But it’s actually not even so much the number of competitions, it’s the level that they’re at because the higher the level the more time they take to design.

Once the Olympic course is finished, will you run a test ride to check it? No, we don’t. But, in my experience in past games, they don’t actually run a test to jump the jumps, but they will run a test to simulate the actual cross country day. But whether or not they’re doing that this time around, I’m not quite sure.

What do you actually do on cross-country day? Well, we have to make sure that nothing has changed with the course. So over the days leading up to the competition, we have to make our final checks. Then, if there is rain, we want to ensure that the footing is going to hold. If not, we have to make preparations to be able to guarantee the footing will hold up throughout the day. Other than that, we basically just watch. If anything needs attending to during the day, we deal with it. We have quite a good crew that’s going to be there on the day, so we can take care of anything that might happen.

And then when it’s all over, do you do just fold up and leave? When it’s over it’s over. Everything gets packed up and put away—and that’s that. Wow! So much work for such a short event. That’s incredible. Sort of, I guess the same can be said about any competition at that level. You put the competition on for a few hours and then you’re done. You’ve prepared years for that.

On another note…

With recent injuries and fatalities on cross-country courses, the issue of safety has really come to the forefront of every conversation. Do you have any thoughts you’d like to share about that? It has always been important, but it’s definitely taking center stage now because there’s a lot more publicity about it. Course designers are making a great effort to ensure the questions asked on course are safe on every level. It’s a huge part of everything we do—everything that I do. You always put safety top, top, top when you’re designing, from the way you set up the track to the jumps you design to the approaches, everything that we do—safety is always a big part of the equation. It has been for quite a long time, I just think it’s much more publicized these days.

What are some safety features you incorporate in your courses? First, we improve the footing to make it safer for the horses. Frangible pins have been used for years now, which basically if you hit a rail hard enough, the jump falls down. Frangible pins release under vertical force. An engineer recently created a device called a “MIM Clip” that allows jumps to give way under horizontal force, which will help prevent a rotational fall. There have been a number of studies on the motion and forces involved in collapsing both these devices.

Those are our two main devices right now, but I think there’s been more and more testing of them to see how they can be used in different situations. There are always people trying to develop new safety devices that will be able to be used to help make the sport safer. Engineers get involved because they understand a lot more of the science of how things work, and you can say how you want something to work and then they start scratching their heads and come up with something.

Bottom line though, you can’t say you’re going to make something a hundred percent safe because that’s just not the world we live in. You’re always going to have some degree of risk; whenever you get on top of a horse, there’s always a degree of risk.

For another excellent (and brand new!) interview with Derek di Grazia, visit Land Rover Kentucky Three-Day on Facebook.

As an equestrian media outlet focused entirely on American horse sport, EQuine AMerica showcases the USA’s equestrian talent (both two-legged and four) in the disciplines of para dressage, dressage, hunters, jumpers, and eventing. We support and promote our nation’s fantastic equine events, products, services, artists, authors, science/tech, philanthropy, and nonprofits through our online magazine and social media platforms. Our mission is to offer you interesting/inspiring short and long-form content in a format that’s beautiful, readable, and relatable.

SOCIAL