—Carina Roselli

Anyone familiar with the historic Devon Horse Show and the elegant Central Park Horse Show may have witnessed a new phenomenon in the sport of Eventing: arena eventing—and it’s quickly become “a thing” in the United States. But what is it? Where did it come from? What do we think of it? Is it good for the horses? The riders? The sport? There’s a lot of talk about it right now, so let’s get in on the conversation.

Online chatter about arena eventing is timestamped as far back as January 2007 (thank you HorseandHound.co.uk and “skye123” wherever you are), but then the chatter quickly turned to something called “Express Eventing.” Primarily in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and sparingly in Germany and Canada, Express Eventing held all three eventing disciplines: dressage, showjumping, and cross country, in a shortened format taking place in one-day of competition within one arena. After the first dressage phase, it was essentially a mad race through what could be an indoor and also outdoor cross country course, then straight back into the arena for the jumping phase with no stopping in between.

I use past tense to describe Express Eventing because it seems to have grown into the UK’s version of arena eventing and no longer exists in its own right. This is at least partly because, in November 2008, British Olympian Mary King lost her Olympic partner Call Again Cavalier during the inaugural Express Eventing International Cup in Cardiff, Wales. The pair fell badly during the arena cross country phase; unfortunately, Call Again appeared to have broken a femur and had to be euthanized. Express Eventing went kind of quiet after that, appearing mostly in less dangerous young rider competitions for the next few years. Then, in 2011, it suddenly reappeared at the UK’s Horse of the Year Show. In 2012, eventing legend William Fox-Pitt agreed to participate in a new team version of Express Eventing at the HorseWorld Live show at the ExCel Arena in London. Fox-Pitt applauded Express Eventing for “taking the sport of eventing to a new and wider audience”—arena eventing in the US is now garnering the same response.

Fast forward to 2014, FEI releases a set of recommendations advising all indoor and arena eventing competitions should be classified at 3* level, should be designed by an experienced 3* eventing course designer, and should follow one of these three formats: (1) Indoor/Arena Derby competition in line with jumping rules, untimed other than the time limit, and pole-topped obstacles, (2) Indoor/Arena Eventing competition untimed with valuation for style, and (3) a two-phase competition where phase one has traditional fixed eventing obstacles and runs for optimum time, and phase two is a jump-off with 6-8 eventing-inspired, but knock-down obstacles. Here we begin to see the evolution of what we now know as “arena eventing.”

Still, even under its new name, riders suffered several nasty falls at an Indoor/Arena Eventing competition in Toronto, Canada in late 2014. Canadian World Equestrian Games rider, Selena O’Hanlon misjudged a Normandy-bank-style obstacle causing her horse, First Romance, to flip over the fence and land on top. O’Hanlon broke her collarbone and spectators broke the internet voicing their concerns all over social media. One scathing post read, “Whatever that was at the Royal Winter Fair, it wasn’t a true depiction of the sport of eventing. They should scrap it or rename it demolition derby.” This started another fresh debate about the risks posed by arena eventing, and the competition went back underground.

All was not lost. In 2016, the UK starts promoting arena eventing again (and the British @ExpressEventing Facebook page goes permanently silent). The next couple of years breathed new life into arena eventing. Australia is back in the game, mixing show jumps and cross country obstacles in the same arena, while the UK format started competitors over stadium jumps and then sent them straight on to a field full of cross country obstacles. In both countries, points seemed to accrue based on optimum time only. Around this same period, arena eventing was quickly making its way across the pond to America.

The first major American showing of arena eventing was at the historic Devon Horse Show and Country Fair in May 2017. Devon press releases described arena eventing as three-day eventing’s cross country phase but made up of solid (but portable) cross country fences of typical shapes mixed with knock-down show jumps of typical varieties. The class was therefore open to eventers and show jumpers alike, but eventers needed to have earned a qualifying score in a 2* CCI competition and jumpers needed to have competed at 1.40m or higher.

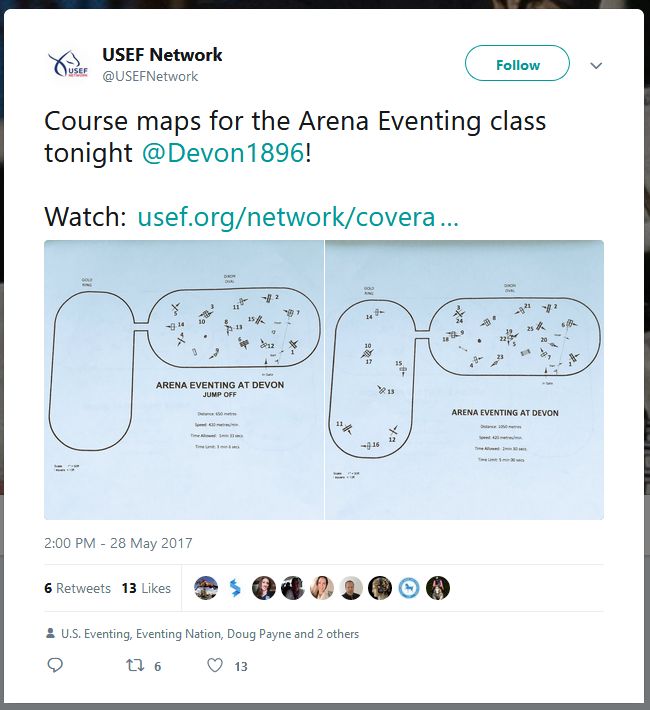

The competition featured 25 jumps, with 15 of them being cross country fences and the rest being show jumps. All obstacles were set at a maximum height of 1.20m or 1.40m for brush fences, with a maximum top spread of 1.60m. And to be sure they got it right, this first American course was designed by Olympic gold medalist Captain Mark Phillips, former coach of the U.S. Olympic Eventing Team. He soon becomes the father of arena eventing in the U.S., designing every major course from then on.

Devon smartly built safety measures into their first go at arena eventing. First, Capt. Phillips made excellent use of Devon’s ample arena space. He designed the course to be tight and demanding in the show’s Dixon Oval arena and then sent riders out into the adjacent Gold Ring where obstacles were set on a loop that really gave the riders a chance to open up their horses’ strides as they would in traditional cross country. From there, they returned to the Dixon Oval to tackle more short distances and turning questions. Second, Capt. Phillips’s design was challenging, but he ensured the first couple of obstacles were knock-down show jumps, not solid pieces, to ease horses into the course.

Lastly, riders were given time and opportunity to acclimate their horses to the arena before competing. Performing in an arena, at night, under lights, with flags and a huge crowd was sure to be quite a different experience for eventing horses used to running through the countryside in the middle of the day. To mitigate fright-related accidents, riders rode or lead their mounts around the fences, under the lights, and past the imposing grandstands looming at the edge of the arena. All three of these measures were smart risk management for everyone involved and will hopefully become a constant in American arena eventing.

There were two rounds of competition. Round 1 was the qualifier, and the top 12 clear rounds under the optimum time moved on to the next round; round 2 was the jump-off, following traditional showjumping format where the fastest clear round ultimately won.

It turned out to be a thrilling and successful night of eventing, where 24 eventers and one hunter/jumper rider took the field to compete for the $50,000 in prize money. The crowd really delighted in the tight competition ending in a close victory for Sara Kozumplik Murphy (USA) and Rubens D’Ysieux in 75.03 seconds. Indeed, the crowd went wild when Murphy reached into her pocket and gave Rubens his usual post-round treat. Practical Horseman later reported that Devon’s arena eventing debut was a “resounding success, captivating the crowd and getting enthusiastic reviews from participants.” And all of this was in the midst of steady rain.

Next came the 2017 Rolex Central Park Horse Show in New York, New York. When several dressage competitors declared they would not be able to perform per usual because of conflicting show schedules, Mark Bellissimo’s International Equestrian Group, LLC (IEG) punted and swiftly rounded up the necessary ingredients for the show’s inaugural arena eventing competition. “Eventers bring a new dimension to the show and it is a great opportunity for the riders to shine against the incredible New York City skyline,” said Bellissimo.

Like Devon, Capt. Mark Phillips designed an Intermediate/CCI 2* level track incorporating both show jumping and cross-country elements, including a bounce-bank and a now-iconic giant Big Apple. One significant difference, however, was that Wollman Arena is tiny by comparison to the combined area of Devon’s grand Dixon Oval and Gold Ring. This course was faster and tighter than either round was at Devon four months before.

Also unlike Devon, the event hosted 24 riders organized into 12 teams of two in a competition termed “Arena Eventing Pairs,” a new derivative of arena eventing. The teams, named after quintessential New York City locales (East Village, Time Square, Chelsea, etc.), worked in a relay race format with both riders in the ring at the same time, with the second rider taking off just as the first made their way through. In a two-round competition, the top six teams that completed the first round track under the time allowed, and without incurring any jumping penalties, moved on to the final, speed-driven, money round to compete for $50,000 in prize money. The winners, Australian riders Dom Schramm on No Objection and Ryan Wood on Alcatraz, finished the second round in 168.31 seconds and earned the brand new title of “U.S. Open Arena Eventing Champions.” With the whole exhibition considered a resounding success, it looks like that title will be up for grabs again this fall.

This past May, after the “immense success” of its 2017 debut, the Devon Horse Show and Country Fair hosted another arena eventing competition. Capt. Mark Phillips again designed the course, consisting of 15 standard (portable) cross country jumps and 10 show jumps, over a 1,000-meter course. Capt. Phillips remarked, “The advantage that Devon has is the use of the two arenas. You have more scope there to do more interesting things on the course than you do at a much smaller arena, like in Toronto or [Wollman Arena in] New York.”

Horse and rider combination requirements and obstacle heights remained the same as last year, but this time forty riders decided to give arena eventing a go. Competition was high, which became especially evident when less than half a second separated the top three rides. Chris Talley and Sandro’s Star took the win as one of only four pairs with no added faults in the first round and one of three pairs who managed a fault-free round in the jump-off. The combination crossed the finish in 78.260 seconds, with last year’s winner, Sara Kozumplik Murphy and Rubens D’Ysieux, not far behind with 78.580 seconds.

Talley commented, “I was a little overwhelmed when I first got in there, and I started walking everything [during course acclimation], and I didn’t know how it was going to ride, and everything rode beautifully.” He added, “Going so quick in a small arena with solid obstacles, you’re not quite sure if the striding works out and everything, but I think they did a wonderful job designing the courses. I think it challenged the horses but rewarded the horses too.” And Murphy again expressed her enthusiasm for Devon’s arena eventing, “The crowd here is like nothing I have ever seen before in this country. Even in Kentucky, it’s not like this carnival atmosphere where so many people are cheering along.”

So, three significant American arena eventing competitions in the last one-and-a-half years—without casualties, without tragedies, and with rave reviews by riders, spectators, and journalists alike. Each event promised and delivered “an action-packed evening and unrivaled opportunity to promote our sport and our riders to a new audience.” Still, it’s clear that everyone realizes (and remembers) arena eventing offers up a whole new recipe for danger.

The 2018 FEI Eventing rules for “Indoor / Arena Cross Country” now state only two options for organizing arena eventing competitions: (1) apply to the FEI to organize the class as an international competition subject to FEI approval, or (2) organize the competition under National rules and under the responsibility of the National Federation to enforce “compulsory minimum requirements.” The rules go on to list those minimum requirements: (1) qualification of athletes requires A, B, or C FEI categorized athletes “to ensure all athletes have adequate experience,” (2) maximum 2* level obstacles and speed related to arena size, and (3) competition format must be either against the clock “ONLY” with knock-down fences or hedges at a minimum 1/3 height of the fixed obstacle, or for optimum time if over fixed obstacles.

When balancing the risks to horse and rider against the rewards of novelty and exposure, I think the overarching question becomes, “Is arena eventing really worth it?” This, of course, breaks down into several other questions. Is it doing great things for the sport of Eventing? Or is it a whole new sport in itself (already with an established pairs team derivative!)? Is it teaching a new audience of spectators about the sport of Eventing? Or is it just misleading and confusing them about traditional Eventing? To that end, does arena eventing encourage a new generation of eventers? Or might it lead to a new generation of just arena eventers (which brings us back to whether it’s a whole new sport in itself)? Undoubtedly, there are many more complex, debatable questions and opinions about this newfangled competition, so EQ AM invites you to join the conversation and tell the equestrian world (and us) what you think.

I will leave you with this interesting tidbit though—at the bottom of page 91 of the 2018 FEI Eventing Rules adding Indoor / Arena Cross Country, under Rule 4, the authors saw fit to remind commentators that large-format video clips are available to show spectators the “real sport.”

As an equestrian media outlet focused entirely on American horse sport, EQuine AMerica showcases the USA’s equestrian talent (both two-legged and four) in the disciplines of para dressage, dressage, hunters, jumpers, and eventing. We support and promote our nation’s fantastic equine events, products, services, artists, authors, science/tech, philanthropy, and nonprofits through our online magazine and social media platforms. Our mission is to offer you interesting/inspiring short and long-form content in a format that’s beautiful, readable, and relatable.

SOCIAL